In his recent column for the New York Times, former Nobel Prize-winning economist Paul Krugman put his finger on why California is a terrifying test case in a housing affordability crisis felt across America. No doubt, as the Covid-19 pandemic persists and ripple effects in the economy linger, housing affordability will continue to be top of mind for working Americans, housing providers, and policymakers alike. As the country continues building back, one of the nation’s leading voices on the economy is sending a clear message on housing affordability: to bring prices down, we must do away with restrictive policies.

As Krugman explains, in recent years California’s economy has grown, but people (especially working people) are still leaving the state in record numbers to escape harmfully high housing prices. In his words:

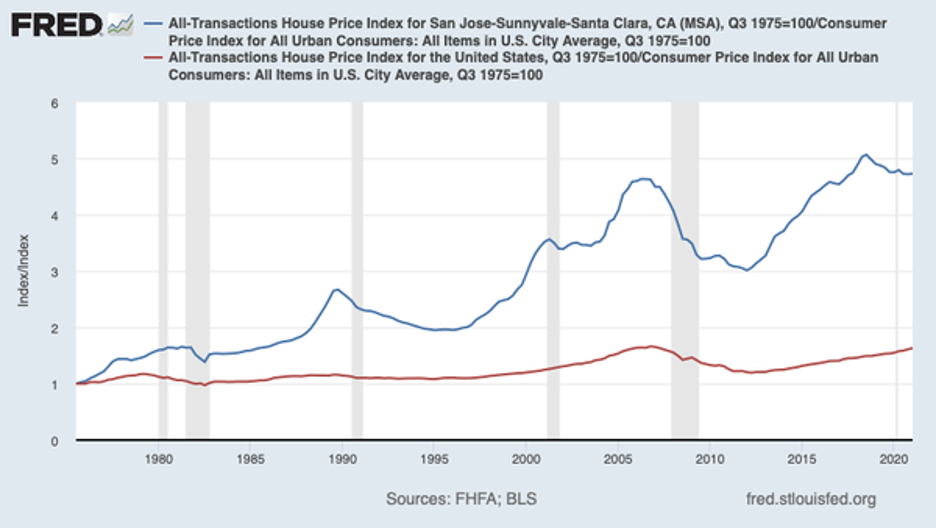

“There’s no great mystery about why this is happening: It’s because of housing. California is very much a NIMBY state, maybe even a BANANA (build absolutely nothing anywhere near anyone) state. The failure to add housing, no matter how high the demand, has collided with the tech boom, causing soaring home prices, even adjusted for inflation:”

If it’s impossible – or impossibly expensive – to build new housing, due to onerous regulations, then the result will be skyrocketing home prices and everyone but the very wealthy being priced out and looking elsewhere to live. Krugman calls this the “gentrification” of California. It’s just common sense that knocking down barriers to building the new housing American communities need – barriers put in place to keep newcomers out, in many cases – is how we make housing more affordable across the board.

In the middle of the country, rent control – a form of restrictive housing policy that has ugly unintended consequences – is being pursued in an extreme form in St. Paul, Minnesota. By not exempting new construction in controlled rents, the proposal will drastically compound the problem Krugman illustrated in California. No developer will risk investing in a project that won’t be able to pay for itself in a location that’s viewed as hostile to new housing construction, at any price point.

Bill Lindeke, an urban geographer and professor with a Ph.D., summarizes his view of the proposal in a column for the Minneapolis Post:

“…it would put St. Paul on its own, with stricter limits on new housing than anywhere else in the country and beyond. While the policy would probably put an end to high spikes in rent, because of the details around exceptions, inflation, and vacancy, it will almost certainly cause other problems that would make the housing crisis even worse.”

Rent control is a bad idea that violates the basic principles of supply and demand, and more restrictions inevitably lead to higher prices. Turning back to Paul Krugman (hardly a right-wing libertarian, by the way) he summed up his thoughts on the subject:

“The analysis of rent control is among the best-understood issues in all of economics, and — among economists, anyway — one of the least controversial. In 1992 a poll of the American Economic Association found 93 percent of its members agreeing that ”a ceiling on rents reduces the quality and quantity of housing.” Almost every freshman-level textbook contains a case study on rent control, using its known adverse side effects to illustrate the principles of supply and demand. Sky-high rents on uncontrolled apartments, because desperate renters have nowhere to go — and the absence of new apartment construction, despite those high rents, because landlords fear that controls will be extended? Predictable.”

In California and St. Paul, we are unfortunately seeing the pursuit of flawed policies. In the end, restrictive policies and extreme rent control proposals will work counter to any solutions that address the root of the problem – a lack of supply. They won’t fix housing affordability challenges, but they will contribute to skyrocketing rents that hurt middle-class and working families.